Gunshot Injuries to Extremities

Objectives

This guideline covers the assessment and treatment of gunshot wounds to the upper and lower extremities.

Scope

This guideline covers the care of extremity gunshot wounds in the deployed setting (Roles 2, and 3). It does not provide guidance on the management of penetrating trauma to the head, spine, thorax, abdomen, or pelvis.

Audience

This guideline contains material relevant from point of wounding through to Role 4. Role 4 practice should be undertaken with reference to both these guidelines and UK standard practice.

Initial Assessment & Management

Background

Extremity gunshot wounds (GSW) are the second most common injury pattern in seen in recent British military activity, behind blast (improvised explosive device) injury. During the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, extremity injuries accounted for 69% of all gunshot wounds in survivors, representing a significant clinical burden to deployed surgical teams. This guideline serves as an aide memoire for how deployed clinicians should manage these injuries. In current and future conflicts, penetrating fragmentation injuries to the extremities, caused by IDF and drone-delivered munitions, are the most common injury mechanisms. This guideline may be applied to fragmentation injury to the extremities as well as gunshot injuries.

Initial assessment

- Assessment and resuscitation should follow the Battlefield Advanced Trauma Life Support (BATLS) algorithm.

- Exsanguinating haemorrhage should be controlled as a life-saving measure to provide time for further assessment, optimisation, and evacuation to the next appropriate care environment.

- In many cases, the initial presentation may be the only opportunity to assess the distal neurovascular status of the limb before the patient is intubated for a prolonged period of time. Therefore, every effort should be made to document perfusion, sensation, and movement of the limb distal to the injury.

Principles

1. Haemorrhage Control

- Ideally established at the point of wounding (See BATLS / UKCCC Manual).

- Uncomplicated wounds without evidence of catastrophic haemorrhage can be managed with simple field dressings, appropriate pressure and limb elevation in the pre-hospital environment.

- Junctional haemorrhage should be managed with advanced dressing techniques, including the use of haemostatic agents, appropriate pressure, and early evacuation to a surgical capability.

- Use of a combat application tourniquet (CAT) for extremity haemorrhage should similarly prompt a decision for early evacuation to a surgical capability to increase probability of life and limb preservation.

- CATs applied before arrival to your facility should be checked for the following:

- ongoing necessity: release under control to determine if significant haemorrhage occurs. If not, remove CAT and apply field dressing.

- location: if the CAT is proven to be necessary, ensure that it is as far down the limb as possible so that healthy tissue is not at risk of ischaemia.

- Resuscitation with blood products, if available, should be considered if not performed during the primary survey. [CGO Transfusion - LINK].

2. Infection Prevention and Treatment

- Prevention of infection starts almost concurrently with haemorrhage control.

- Early systemic antibiotics should be administered particularly to cover gram positive organisms (See Deployed Antimicrobial Guidelines) as GSW are often contaminated with microorganisms, environmental debris, and clothing.

- Increasing delays to antibiotic administration are associated with increased incidence of infection, so should be administered at the earliest opportunity following wounding. Surgical management should follow the CGO for Wound Excision.

3. Skeletal stabilisation

- Extremity GSW complicated by a fracture may need to be stabilised with either plaster or external fixation (see CGO for External Fixation Configurations (LINK)).

- Forward of R2, the extremity should be aligned and splinted (e.g. upper limb using the SAM splint or femur using the Kendrick Extrication Device).

- In cases with significant soft tissue wounding without associated fracture, splintage may still be appropriate to aid with analgesia and haemorrhage control.

Other considerations include assessment of distal vascularity, neurological function, and compartment syndrome [See CGO on Acute Compartment Syndrome and Fasciotomy] which should be serially repeated and documented.

Advanced Assessment & Management

On receipt of the patient at higher role surgical facility, the primary survey should be repeated. At this stage, characterisation of the injury can be more thoroughly carried out.

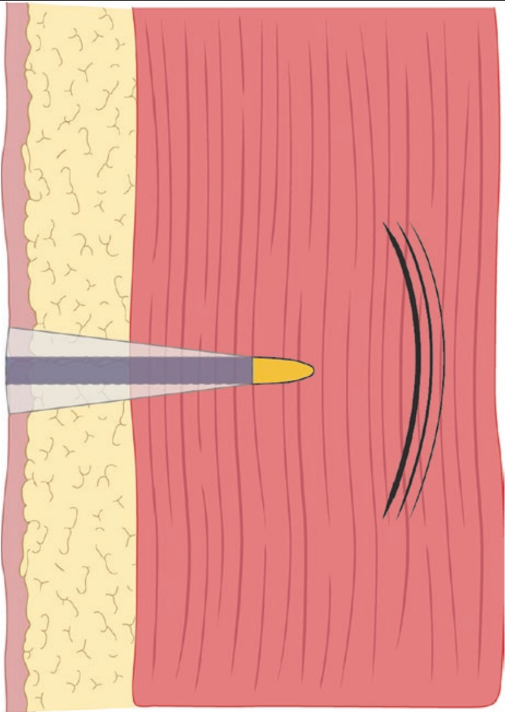

An understanding of the mechanism of GSW is paramount, as the wound pattern must be determined from thorough clinical assessment. When a projectile strikes the casualty, it crushes and lacerates its path through the tissues (Figure 1). Soft tissues then radially accelerate away from the tract in the wake of the projectile forming a temporary cavity, with negative pressure drawing contaminants in via the entrance (and possibly also exit) wound. This temporary cavity then collapses under the elastic recoil of the tissues and oscillates until the kinetic energy has been dissipated within the tissues.

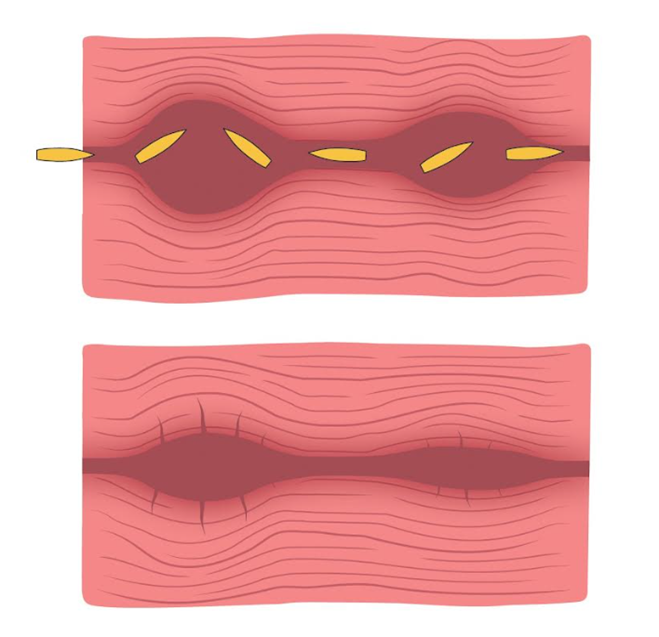

The resultant permanent cavity left behind is then what the clinician will be faced with and must decide to what extent surgery will be used to treat the wound (figure 2). It should be remembered that wounding patterns from projectiles are subject to influence from projectile physical characteristics such as calibre, deformation, fragmentation, as well as the clothing layers worn by the casualty, and the potential involvement of bone or neurovascular structures, all of which add to the complexity of the wound. Further detail on wound ballistics is beyond the scope of this document.

Imaging

Radiographic imaging should be taken with radiopaque markers over entry and exit wounds. This permits assessment of retained fragments and associated skeletal injury. If available, CT imaging and angiographic studies should be considered for the more complex wound profiles i.e. those with associated fractures, based on the clinical assessment.

Simple Vs Complex Wounds

When combining the clinical assessment and radiographic imaging of the wound, it should be possible to stratify the injuries into simple and complex categories. It is more important to treat the wound, rather than focus on the weapon system that inflicted the injury.

Simple wounds:

These involve limited energy transfer from the projectile to the patient (limited or no cavitation occurs) and can be defined by:

- No neurological or vascular compromise

- No associated complex fractures (see “Fractures” below)

A ‘through and through’ wound with small entry and exit wounds that approximately match the diameter of the projectile ie <10mm, with no adverse features would be an example of such an injury. Retention of an intact projectile implies a greater delivery of kinetic energy within the wound, though given the variability of projectile characteristics upon when the GSW was sustained, is not necessarily complex and does not in itself mandate surgical exploration. However, projectile deformation or fragmentation should be seen as a feature of a complex wound where the projectile surface area for kinetic energy delivery to tissues is increased and therefore the potential for substantial tissue injury is far greater and may be masked outwardly from first clinical inspection.

Simple wounds can be managed non-surgically, as any tissue necrosis is likely to be minimal and limited to the permanent tract, rather than the extensive tissue necrosis seen in more complex wounds.

In general, an extremity gunshot wound associated with a fracture is classified as Complex. However, some fractures can be consistent with low energy transfer and do not automatically cause the wound to be classified as “Complex”. If the wound is otherwise classified as Simple and has an underlying fracture with the following characteristics, it may be treated as Simple:

- “Drill Hole” fracture

- Incomplete or unicortical fractures

- Chip fractures

Management of Simple Wounds:

- Oral antibiotics [CGO Deployed Antimicrobial guidelines] as soon as possible after point of wounding

- Copious irrigation - should take place no further forward than R2. Removal of gross contamination is the limit of wound cleaning advised in R1.

- Dressings with standard wound care

- Splintage with incomplete casts or removable splints should be considered for comfort and promotion of wound healing

- Do not close simple extremity gunshot wounds due to the risk of infection

- Analgesia

- Drill Hole fractures should be managed with copious irrigation and flossing if the morphology of the injury tract permits. Protect the patient's weight bearing until senior orthopaedic surgical review has been completed.

Complex Wounds:

Involve significant energy transfer to the patient. Defined by presence of the following:

- Large entrance or exit wounds ie >10mm, and that are irregular in shape (though it should be remembered that small entrance and exit wounds may be masking substantial tissue injury beneath)

- Neurovascular injuries

- Fractures (see below)

- Heavy contamination

- Projectile fragmentation

- Significant haemorrhage

These require surgical extension of the wound, copious irrigation with low pressure saline and debridement of tracts by ‘flossing’ with damp gauze or with surgical excision if indicated (see CGO on Wound Excision). Should sterile saline be logistically constrained, potable water could be considered, with saline used for the final wash.

Coverage with topical negative pressure dressings (if available) is useful for managing wounds with high exudate output or complex morphology but are not mandatory. Non-adherent base layer and then packing with loose gauze can be used if negative pressure units are not available. Other specialist dressings are not indicated.

Limbs with significant tissue disruption, vascular injury, or necrosis should be considered for myofascial compartment release due to the potential for compartment syndrome. [See CGO Acute Compartment Syndrome and Fasciotomy]

Fractures: Fractures associated with GSW are, by definition, open and should be managed with appropriate debridement of devitalised bone fragments, early intravenous antibiotic administration, and external fixation/plaster or splint immobilization as indicated. Under no circumstances should internal fixation be attempted within the deployed setting. Plaster casts, if used, must be incomplete (backslab) or fully split down to skin if a cylinder cast is required in order to allow for tissue swelling and minimise the risk of compartment syndrome. Vascular shunting or repair requires a stable limb Therefore, skeletal stabilisation with plaster or external fixation is mandatory in the context of fractures with associated vascular injury requiring repair. [CGO External fixation].

Further wound excision and dressing changes should be guided by logistic constraints, need for evacuation, and patient physiological status. Clean wounds could be considered for closure at a second exploration (see CGO Wound Excision). Heavily contaminated wounds with further necrosis or marginal tissue changes may require several further reviews in the theatre setting before delayed primary closure is appropriate. Healing by secondary intention is reasonable if wound factors make delayed primary closure inappropriate.

Reconstructive considerations should be identified and documented early, particularly in complex wounds with large volume tissue loss, though will not be further considered within this document.

Special considerations

Retained projectiles and fragments: Projectile fragments retained in soft tissue are not an absolute indication for debridement, irrespective of the metal content of the projectile, as meticulous retrieval of all fragments can lead to iatrogenic injury during tissue exploration. However, projectile deformation and / or fragmentation is associated with higher complexity injury and increased kinetic energy transfer, making the requirement for debridement more likely.

It should also be remembered that following the collapse of a temporary cavity from the initial wounding, any air or microbes drawn into the wound could then be forced along the path of least resistance rather than the route through which they entered. They may be distributed along tissue planes and potential spaces remote from the actual site of injury. A high index of suspicion for exploration of these areas must be maintained in the context of casualties deteriorating or not demonstrating any clinical improvement after the initial wound debridement has been completed.

Intra-articular retained fragments can be associated with lead toxicity (for lead-based projectiles) and consideration should be given to early surgical removal. Intra-articular wounds are also at risk of septic arthritis and should be irrigated thoroughly.

Amputation: Formal amputation, with the fashioning of flaps and primary closure, is not recognised as an appropriate procedure in the deployed surgical setting. Thorough surgical excision of a wound may include removing part, or all, of a limb and this is performed according to the principles described in the CGO Wound Excision but this is not the same as performing a formal amputation.

Vascular injury: Vascular injury can be occult and must be specifically looked for with serial examination. Intimal injuries are unlikely to be detected on physical examination alone and may require dedicated vascular imaging to assess. Vascular injury in the forward or damage control setting is often managed with temporary shunts prior to definitive vascular repair. Vascular injury and repair should be accompanied by distal myofascial release and requires skeletal stability to be performed in order to protect the repair.

Nerve Injury: See CGO Wound Excision for full details of management of nerve injuries as part of conflict-related wounds. In summary:

- Carry out and document a detailed neurological examination at first presentation and pre- / post-surgical wound management

- Document the condition of nerves encountered during surgical wound excision

- Do not repair nerves at primary wound exicsion

- Do not tag wounds

- Consider nerve repair at definitive closure if skill set and resources allow. This is not mandatory.

Compartment syndrome: [See CGO Compartment Syndrome]

Hands: Given the importance of the hand as a vital functional unit, consideration should be given to more limited debridement of gunshot wounds to the hand. Small amounts of retained tissue can be critical in preserving function in subsequent reconstructive efforts. Where tissue in the hand is of questionable viability, there is potential for it to show signs of recovery by the time of the second look and should be given the chance to declare itself wherever possible.

Feet: The principles of managing foot GSW mirror those for managing GSW of the hand. This is an important functional unit that should favour, where possible, limited debridement in order to preserve tissue for coverage and reconstruction. Weight-bearing status needs to be considered, and non-weight bearing on the injured limb is likely to be appropriate in initial management and recovery phases. Consider splintage or plaster casts to protect the limb even in the absence of fractures.

Prolonged Casualty Care

Prolonged field care without surgical capability should focus on resuscitation, antibiotic therapy, permission of wound drainage and simple wound care. Complex wounds cannot be adequately managed outside of a surgical capability. In situations where surgical facilities are overmatched, patients with “simple” gunshot wounds (see above) may be managed in Role 1 with simple wound cleaning, oral antibiotics, and dressings (which is consistent with civilian practice in many healthcare systems). These patients should be evacuated for specialist assessment and further management when circumstances allow.

Paediatric Considerations

The principles of paediatric gunshot wound management in the forward surgical environment, whilst emotive, are not practically different from in adults. Analgesia, medication dosing, and resuscitation require different parameters that should be reviewed as required. [CGO principles of paediatric extremity trauma]